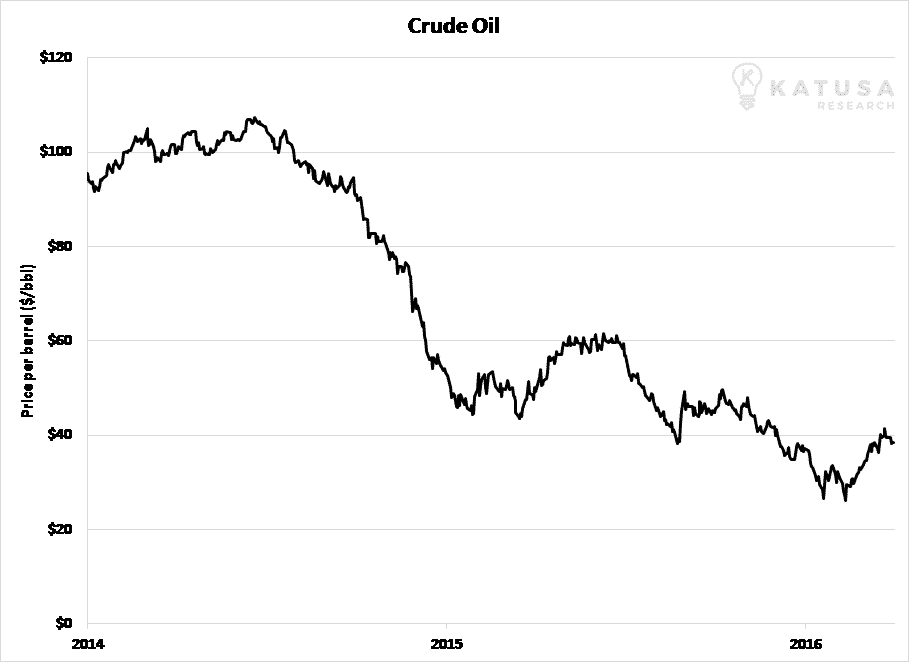

On June 18, 2014, the price of crude oil traded for $106 a barrel.

Just 19 months later, the price had plummeted 73% to $28 per barrel.

After reaching $28 per barrel, oil then skyrocketed 88% in just four months.

What sort of asset regularly goes through massive price swings like that?

Not your house…and not government bonds.

Natural resources do.

More than any other asset, natural resource prices go through extraordinary booms and busts. One year, the value of a resource like oil, silver, or copper will skyrocket 75%. The next year, it will fall 50%.

Because natural resources cycle through huge booms and busts, they are said to be “cyclical” assets.

Many things in our world move in cycles. The weather moves in cycles. The planets revolve around the sun in cycles. Animals move around their habitats in cycles.

You also see cycles in the financial markets…especially in the natural resource sector.

Because resources cycle through booms and busts, they are said to be “cyclical” assets. Understanding this concept is by far the biggest key to making huge returns in the natural resource sector.

If you don’t understand how resource cyclicality works, nothing else you do will matter. It’s the most important thing.

The cyclicality of natural resources contrasts with “noncyclical” businesses like those that sell toothpaste, toilet paper, or food.

Demand for everyday things like these is relatively constant. No matter what is happening with the economy, you’re probably going to brush your teeth, go to the bathroom, and eat lunch.

Natural resources, however, exhibit extreme cyclicality. And their massive price moves produce massive opportunities to profit.

In the year 2000, for example, shares in the world’s largest uranium mining company, Cameco, traded for $1.35 per share. Seven years later, Cameco shares had increased in value by 3,600%, reaching $50 per share.

Gains like that are possible in natural resources because of their unique supply/demand dynamics…

When the price of a natural resource soars, it encourages lots of new production. Natural resource producers always want to cash in on high prices.

For example, if corn soars in price, farmers will plant a lot more corn.

If the price of oil soars, oil companies will pump a lot more oil.

This natural response to high prices leads to an increase in the supply of the natural resource.

The soaring price also encourages consumers of that resource to find cheaper replacements. For example, if gasoline were to triple in price, you would be more likely to take the bus or cut back on car trips. If the price of coffee soars, you might start drinking tea instead.

This natural response to high prices leads to a decrease in demand for the natural resource.

When the supply of a natural resource increases and demand for it decreases, you get much lower prices. You get a bust. In other words, a resource bull market eventually sows the seeds of its own destruction.

When a boom ends, it’s not unusual to see the value of a natural resource plummet in a short amount of time. Remember, the price of oil plummeted 73% in less than two years.

A natural resource boom is the mirror image.

When the price of a natural resource is very low, it discourages production.

After all, why ramp up production if the price is in the toilet?

The farmers who planted as much corn as they could when prices were sky high will plant a lot less corn if prices are low.

The oil companies that produced as much oil as they could when prices were high will produce less if prices are low.

Low prices also encourage consumption. You’re probably going to drive more if the price of gasoline plummets.

When the supply of a natural resource shrinks and demand climbs, you get a boom. In other words, a resource bear market eventually sows the seeds of its own destruction.

Recent history in the copper market provides a great example of this.

During the 1990s, the price of copper was very low. This led to decreased production. Meanwhile, demand for the cheap resource soared.

This “increased demand/decreased supply” sandwich caused the price of copper to soar from $0.75 per pound in 2003 to $4 per pound in 2008 (a 400%+ gain).

When a natural resource moves in price, the share price movements of natural resource producers are amplified. During the big 2003 – 2007 copper rally, the large copper miner Freeport-McMoRan skyrocketed from $3.50 per share to over $50 per share during this time–a 1,300%+ increase.

By now, you surely see what we need to do as resource investors.

***We need to invest in individual resource markets when prices are very cheap and depressed, yet poised to climb.

This setup led to the 1,300% gain in Freeport McMoRan…and the 3,600% return in Cameco.

To make huge gains in natural resources, we have to buy assets after bear markets…when they are very cheap and depressed.

In these situations, you’ll be buying something the investment crowd doesn’t want. But that’s a sign you’re probably doing the right thing.

When the crowd finally realizes a boom after it has already started, it will bid the price of your assets up to incredible heights. That’s when you–the contrarian–can sell for huge profits.

Resource markets are extremely cyclical.

Their enormous booms and busts make it tough for most people to make money in them.

But extreme resource cyclicality offers huge opportunity to those of us who understand it.

Regards,

Marin Katusa