Private placements are in high demand with wealthy, knowledgeable investors. They allow you to buy large blocks of stock at discounted prices… while getting massive upside “kickers” in the form of warrants.

Private placements are one of the most attractive investment vehicles on the planet, because of the terms and advantages they offer. Despite this, you’ll never see these deals featured on the front page of the Wall Street Journal. People on mainstream financial television never talk about them.

Table of Contents

- 1. What is a Private Placement?

- 2. Why Would I Want To Buy a Private Placement?

- 3. How Risky is a Private Placement?

- 4. Why Do Companies Offer Private Placements?

- 5. What Do I Need to Participate in a Private Placement?

- 6. What’s the Difference Between a Canadian and US Private Placement?

- 7. Types of Private Placements

- 8. What Are Reg A and Reg D Offerings?

- 9. What Are Some Common Buzzwords Used in Private Placements?

- 10. Private Placement vs IPO (Initial Public Offering): What’s the Difference?

- 11. How Do I Buy a Private Placement?

- 12. Where Can I Find Private Placements to Buy?

- 13. External Resources

1. What is a Private Placement?

A private placement is an opportunity for an investor to buy shares of a company from the company itself.

Most investors know that you can buy and sell shares in the open market.

Few investors know that you can privately buy shares directly from both publicly traded as well as private companies.

These deals come straight from within the company and don’t take place on stock exchanges. So you can’t look up their details or pricing on websites like Yahoo! Finance.

The money involved in many private placements is often tiny compared to the money involved in a big name IPO like Tesla Motors. This lack of mainstream popularity turns many folks off. They simply aren’t comfortable with investments that aren’t widely covered by mainstream media .

Sometimes, private placements can also be “debt offerings”. This is where the company sells interest-bearing instruments directly to private investors, instead of issuing new shares to them. This guide will focus on “equity offerings”. This is where newly created shares get issued to investors instead of debt.

2. Why Would I Want to Buy a Private Placement?

Large investors love one thing about private placements. They can negotiate the buy price per share and the total amount invested with the company, in advance. They can get large share positions and don’t have to deal with the market’s day-to-day fluctuations.

Depending on the securities regulator, this could be as high as a 20% discount to the current market price. The exact price used can be calculated in several ways, but it’s most commonly done relative to VWAP (Volume Weighted Adjusted Pricing).

For example, let’s suppose a stock was trading at 25 cents for a period of time, before quickly rising to 30 cents. The company would likely be permitted to issue a private placement offering for 25 cents, especially if there was no other material news. Of course, the pricing would still be subject to regulatory approval.

This encourages larger and more sophisticated investors to participate. This stops them from sending the share price higher themselves while they’re still trying to acquire their full position.

Savvy investors, in particular, love private placements. They’re not just getting shares at a discount to the public market price. They can also receive warrants for large added upside at no further risk to themselves.

So, what are warrants, and why do savvy investors love them so much?

For those of you who have experience with derivatives, warrants are very similar to options.

In other words, warrants let their holder buy more shares of the company if they want. When you consider that they come packaged in most private placements for free, it sounds like a pretty good deal, right?

The price at which warrants allow their holders to buy additional shares at is called the strike price. But usually the strike price is set above current market prices. After all, they’re meant to be extra upside, so there’s no point if the strike price is too low – they’d be no different from ordinary shares.

If a company does well after a private placement financing, warrants can greatly increase the upside for the investor. And sometimes, the warrants themselves are listed and publicly traded. In other words, some warrants can be bought and sold on the open market just like regular shares. If so, this means private placement investors can also consider mitigating risk by selling their warrants.

3. How Risky is a Private Placement?

Buying a private placement comes with one main extra risk when compared to buying in the open market. But overall it may not be riskier.

All the usual risks associated with buying a publicly listed company are still there when you buy a private placement.

For example, private placement risks include:

-

- The company might fail and go bankrupt.

- There might not be enough liquidity for you to easily exit the position.

- It may take longer for your investment thesis to play out than you initially projected.

- If you’re buying into a private company, there’s a chance the company may never go public.

However, some risks are actually alleviated when you buy in a private placement versus buying in the open market:

-

- You get to lock in a fixed purchase price, without having to worry about market volatility.

- You get a discount to the current market price.

- You may get free upside in the form of warrants.

- You don’t have to pay a commission to your broker.

That said, there’s one main extra risk that’s unique to private placements when compared to buying stock the regular way. And it’s known as the Hold Period.

What this means is that for the duration of the hold period, you’re unable to sell your shares. They’re effectively locked up.

Most of the time, this hold period is only 4 months long. But, things can often change quite quickly in the markets.

A new macroeconomic shift could happen. And it could force you to change your investment outlook and your portfolio. Let’s say this new market trend makes you decide to sell your position in a particular company…

You would easily be able to do so if you had bought the shares on the open market. But if you purchased them in a private placement, you might still be subject to the hold period. Thus you’d be unable to sell your position.

Such occurrences should be unlikely – after all, you would’ve taken both macro and micro considerations into account before making an investment in a company, whether on the open market or in a private placement. Still, black swans do happen, so the risk is there.

Beyond the hold period risk, the other features of private placements alleviate risk when compared to buying a stock position the regular way. That’s why if the hold period risk is minimal for a particular company you’ve chosen (strong company fundamentals, long term bullish outlook for the sector), private placements can be more attractive buying opportunities than picking up stock on the open market.

4. Why Do Companies Offer Private Placements?

When a company needs to raise money to do things like:

-

- Expand their sales team,

- Take over another company,

- Drill for oil,

- Develop a gold mine, or

- Fund a team of video game developers…

…they often do it through private placements.

Many times, a company finds that it needs a large chunk of capital in order to expand. Or even just to sustain their operations.

Offering a private placement is one of the best ways for them to do so. Taking a business loan from a bank would incur interest expenses, for instance. And what if the company doesn’t have any significant cash flow from its operations? Banks wouldn’t be willing to let them borrow much anyway.

There are other solutions to the capital problem. There are joint ventures, corporate debt issuance, and others. But they also all tend to come with more drawbacks than when compared to private placements.

That’s why companies are so willing to use private placements as a capital raising tool. It’s another reason why private placements are usually priced at a discount to the company’s current market price. It helps make the opportunity more attractive to prospective investors.

When terms are more appealing to investors, companies have an easier time raising the total amount of capital they need.

Of course, private placements do have their drawbacks for the company as well. By issuing new shares, the company dilutes its current share structure. This means that previous shareholders of the company now own less of it.

This can be a concern for entities trying to maintain a controlling interest in the company. But for most investors this isn’t an issue, especially if they didn’t already own a position in the company prior to investing in the private placement.

Warrants operate in a similar fashion for the companies issuing them. When warrants are exercised and additional shares purchased, they can further dilute the company’s stock.

However, warrants always have their strike price set higher than the market price of the stock. So in a way, when warrants get exercised, the company gets to raise money at a better price than they did in their financing.

On the whole, private placements are still generally considered a win-win for both companies and investors alike.

5. What Do I Need to Participate in a Private Placement?

In the USA, Canada and other first world countries, you must be an accredited investor to participate in a private placement.

Securities regulators want to make sure that investors choosing to get into private placements know the risks (and there are many). The terms, rewards and gains might be very lucrative. But you could lose your entire investment.

Regulators want to make sure that novice investors don’t lose their shirts investing in private placements. It’s easy for a cheap deal to seduce a novice investor. And then when that cheap deal blows up, said novice investor comes back to the company or regulator with litigation. So, regulators created the Accredited rule (or exemption).

Long story short, here’s what it means: You must check at least one of the boxes in the private placement forms that tells the company you’re an accredited investor. Then the company raising the funds knows you’re qualified to get in the deal.

Some of the commonly used criteria to qualify as an accredited investor are as follows:

Have a salary of $200,000 per year, or $300,000 per year combined with your spouse for the last 2 calendar years, with the expectation that it’ll stay there for the current year as well.

Own $5 million in total assets including real estate, net of debt (Canada only).

You can see that these criteria tend to filter out the people that don’t have a lot of money. And you might think it’s “not fair” that only these accredited investors get to participate in private placements and financing deals. But, there are other options for non-accredited investors that we’ll get to later on in this guide.

Since private placements can be extremely attractive investment vehicles…sometimes companies end up with too many people trying to get in. This happens because companies plan to raise a set amount of capital when they announce a private placement – say, $5 million dollars.

Raising more money than planned for is not necessarily a good thing for a company. They won’t have a plan in place for proper use of funds. Their stock becomes diluted and they can draw the ire of securities regulators.

In particular, publicly listed companies looking to finance themselves through a private placement must obtain approval from their exchange. And this approval is contingent on certain pricing and gross proceeds limitations.

Because of this, let’s say a company gets requests for $10 million worth of a private placement from interested investors. But if they’re only trying (or allowed) to raise $5 million, cutbacks will happen.

Sometimes this happens evenly. In our example, by cutting every investors’ requested allocation in half, the company would be able to hit their $5 million target.

Of course, this isn’t always how it’s done.

Often times private placements are a chance for management and institutional investors to jump in or back up the truck. So to go back to our previous example, let’s pretend that of the interested $10 million, $4 million came from management’s own pockets, plus a large hedge fund.

In this theoretical case, it’s entirely possible that the company would choose to fill the $4 million worth of allocations first. Afterwards, they’d chop up the remaining $6 million of requests to fit into the last $1 million worth of space. This would cause all of the other “regular” investors to only receive 1/6th of their requested allocation.

At the end of the day, the company raising the money has the final say in who gets how much of their private placement. Like with hot IPOs, a popular private placement can get too much demand for the company to fulfill all the orders they get. This means that some investors can get preferential treatment.

In any case, let’s say there’s a company you’ve done your due diligence on and are willing to invest in. If they’re offering a private placement, there’s no harm in asking for an allocation.

5.1 Accreditation Differences Between Canada and the US

Now regardless of whether you’re a US investor or a Canadian investor, the accredited investor regulations still apply to you.

If you’re American, then the SEC (Securities and Exchange Commission) lays out the rules for accredited investors in Rule 501 of Regulation D of the Securities Act. The picture below, from the US Financial Industry Regulatory Authority (FINRA), highlights the most common criteria from the Act:

If you’re Canadian, you’ll find the same information in National Instrument 45-106.

The criteria we listed above are the most commonly used ones for individual investors. And they are very similar between the two countries. But if you’re not clear on whether or not you qualify as an accredited investor, read up on your country’s exact definitions.

6. What’s the Difference Between a Canadian and US Private Placement?

Whether you’re trying to get into a private placement on the Toronto Stock Exchange or the New York Stock Exchange, the process is similar.

If you’re an American looking to get into a Canadian private placement or vice versa… the first thing to do is to make sure that the placement is open to foreign investors.

The other thing to note is to make sure that you satisfy the accredited investor status in your own country.

There are subtle differences in some of the criteria to qualify between Canada and the USA. If you’re Canadian and want to participate in a US private placement, make sure you satisfy the Canadian accredited investor requirements. This is because that US private placement will have forms for Canadian investors that follow Canadian regulations.

7. Types of Private Placements

There are many types of private placements that companies do to raise funds.

7.1 Brokered Private Placement

In a brokered private placement, a brokerage house acts as a middleman between the company and investors. The broker raises the money from clients and directs it to the company. The broker receives a commission in the 6% to 10% range for performing this service.

This usually happens when it’s a large financial raise. Or when a small cap company needs the help of a broker to drum up interest.

Some brokers have large client bases who like to participate in private placements. Getting access to a large base of investors can make it attractive for a company to go down the brokered financing route.

The management teams who have large networks can go down the “non-brokered” financing route. This way they cut out the middleman (broker) to save on financing costs.

7.2 Non-Brokered Private Placement

In a non-brokered private placement, the investors place their money directly with the company. This saves a lot of money on fees for the company.

Non-brokered financings are typically done by companies with access to good contacts and networks. They have “reach,” so they don’t need to pay a broker.

7.3 Bought Deal Financing (Private Placement)

A bought deal financing is when an underwriter (like a brokerage) decides to buy the whole financing allotment, at a set price, from the company issuing the shares. Those shares are then re-sold to the public or their clients.

8. What are Reg A and Reg D Offerings?

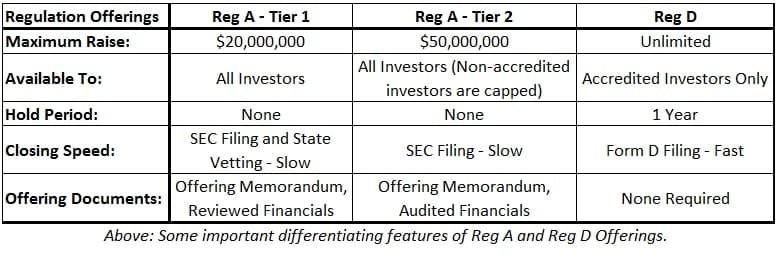

If you’re a veteran of the private placement world, you’ve seen the terms “Reg A” and “Reg D” thrown around on occasion. Those are short for “Regulation A” and “Regulation D”.

These types of offerings are special SEC exemptions for private companies trying to raise money from investors.

Here’s what sets Reg A and Reg D offerings apart from regular private placements. Both regulations allow companies to forego having to register their stock with the SEC. This means less paperwork, less time, and less cost for the company. This is especially true when compared to an IPO. This can help the company scope out investor interest without spending too much on legal and professional fees before actually going public.

Companies looking to do Reg A and Reg D offerings still need to register the financing itself with the SEC and get approval. Thus they’re not inherently more risky than any other private placement.

There are good reasons for a private company to go with a Reg A placement to raise capital instead of a more “traditional” method. For example, Reg A is more favorable in a seed round with private investors.

In other words, Reg A and Reg D offerings are just private placements under a different name.

So, what’s the difference between Reg A and Reg D?

Well, there are a lot of fine details that differentiate the two – but from the investor’s perspective, here are the highlights:

8.1 Regulation A Offerings:

-

- Are capped at $50 million.

- Under $20 million, investors don’t have to be accredited to participate.

- Between $20-50 million, non-accredited investors can still participate, but their maximum allocation is capped based on the higher of 10% of their net income or 10% of their net worth.

- Accredited investors are not capped.

In other words, even if you’re not an accredited investor, Reg A offerings can still be a great way for you to get access to the benefits associated with a private placement. Provided, as usual, that you would be willing to buy into the company without a private placement involved.

8.2 Regulation D Offerings:

-

- Are generally only open to accredited investors.

Technically, up to 35 non-accredited investors may participate. But the amount of extra headache and cost involved generally makes it not worthwhile for companies to include non-accredited investors in their Reg D offerings.

That’s why it’s best to think of Reg D offerings as only being available to accredited investors… Unless specifically mentioned otherwise.

8.3 Regulation A+ Offerings:

Now if you’ve been around the private placement block, you may also have seen the term “Reg A+” thrown around as well.

This came about as the result of a change that the SEC made to the Reg A guidelines in 2015. It expanded Reg A into its current split between the $0-20 million tier and $20-50 million tier of capital raises. This new expansion to the original Reg A rules is what’s known as Reg A+.

Reg A+ is the “new” Reg A. But many people continue to refer to them as Reg A offerings.

So regardless of whether a company announces a new placement as a Reg A or Reg A+ offering… it’s still the same thing.

In summary, the table below highlights the important differences between the different Regulations.

9. What Are Some Common Buzzwords Used in Private Placements?

Accredited Investor

Debt Offering

Equity Offering

Exercise

Expiry (or Expiry Date)

Free Trading

Hold Period

Offering Memorandum

A legal document that must be provided by private companies doing a private placement. Also known as a Private Placement Memorandum or Offering Circular.

These documents provide details on the company’s business plan and the risks involved with investing in the company. Though nominally provided as a legal requirement to allow the company to raise money through an exemption such as Reg D, offering memorandums can be used as part of an investor’s due diligence. This is because they’re typically more factual and less forward-looking than other presentations and investor material that a company might provide, since they’re legal documents.

Note that memorandums are only issued by private companies. For a publicly listed company, the equivalent is a Prospectus.

Private Placement

Prospectus

Reg A, Reg A+, Reg D

Rule 144A

A special type of offering for private companies. In this type of offering, the company directly assigns the full allocation of its private placement to one or more banks or brokers. The latter then resell the securities to “qualified institutional buyers”.

Rule 144A offerings are similar to Reg A and Reg D offerings in that they offer simpler, cheaper alternatives to raising capital for private companies who aren’t ready to IPO yet. More money is raised through Reg D offerings than Rule 144A offerings. And Rule 144A raises tend to be debt offerings by larger issuers. Rule 144A offerings also often contain a provision for foreign (non-US) investors, known as Reg S.

Strike Price

Warrants

The right, but not the obligation, to purchase additional shares of the company at a pre-set fixed price, the (Strike Price).

Many, but not all, private placements come with warrants. Warrants always come with an Expiry Date – once this date has passed, the warrant is no longer valid.

10. Private Placement vs IPO: What’s the Difference?

If you’re a new investor you may not have heard of private placements before, but you’ve almost certainly heard of IPOs. Both are ways for companies to raise the capital they need to run their business. So, what’s the difference?

IPO stands for Initial Public Offering. IPOs happen when private companies offer shares to the public for the first time. Because of this, IPOs are also usually connected with new listings on stock exchanges.

In contrast, private placements can happen whenever a company needs to raise capital – whether it’s already a public company, or a private company that plans on staying private.

For some sectors – such as the resource industry – seeing multiple private placements from the same company is a common occurrence. A common example would be the case of a small cap junior mining company trying to drill out its projects.

11. How Do I Buy a Private Placement?

The process of buying into a private placement is very simple and straightforward.

As mentioned in the What Do I Need to Participate in a Private Placement section… the first thing you need to do is to make sure you qualify as an Accredited Investor.

If you know you do, then the next step is to make sure that the private placement you’re trying to get into is open to residents of your country.

If you’re a US or Canadian citizen trying to get into a private placement for a company listed on any North American exchange, this is practically a foregone conclusion. Only residents of Quebec may face additional challenges.

If you don’t live in either of those two countries though, and the private placement you’re looking at is for a company that’s not based in your own country, this is something you need to verify.

Once that’s done, all that’s left is to ask the company for your desired allocation. Then, of course, make sure that you have enough cash set aside to actually pay for your full allocation in case you get it.

Past this point is the mere formalities:

- Filling out your subscription documents (which are the legal paperwork the company needs to process your private placement order), and

- Sending the money to the company, usually done via bank draft or wire transfer.

To illustrate this example, let’s look at how this would go down:

11.1 Example of a Private Placement Purchase

Let’s say that Joe Smith, living in New York, wants to buy shares in the TSX-listed company Katusa Gold.

He’s done his homework and thinks Katusa Gold is a stock he wants in his portfolio. And, Katusa Gold has just put out a news release stating that they’re looking to raise CAD$5 million dollars through a private placement in order to finance an upcoming drill program.

Joe thinks that this private placement has good terms and is a good entry point for him to add Katusa Gold to his stock portfolio. So the first thing Joe asks himself is this: “Am I an Accredited Investor?”

Joe’s annual income in the past two years, as reported on his tax returns filed with the IRS, was USD$250,000. He’s still working at the same job, and doesn’t expect to get fired anytime soon, so he can reasonably assume he’s going to make the same amount, more or less, this year.

In addition, Joe also owns a sizable investment portfolio worth USD$1.2 million.

Joe recognizes that he qualifies as an accredited investor under two different criteria. Only one is necessary, so Joe knows he’s good on that front.

The next thing Joe does is that he contacts the company directly, asking if this Canadian private placement is open to US residents. The company confirms that it is.

Joe places his request for CAD$50,000 worth of the private placement (note the company asked for funds in Canadian Dollars). He does this both by phone and by email in order to make sure that his order isn’t missed by accident. The company confirms its receipt of his order back to him.

A few days later, Joe gets an email back from Katusa Gold. Unfortunately, since Katusa Gold is a hot stock, the private placement was oversubscribed. Subsequently, Joe’s allocation was cut back to CAD$20,000 in order to make sure everybody could get a piece.

Attached to the email is a PDF – a set of subscription documents, along with payment information. Joe fills out the subscription documents on his computer and signs them. He then emails them back to the company.

He then walks over to his local bank, where he uses the payment information provided to send the company a wire transfer for CAD$20,000 – making sure to take the foreign exchange rate into account, as he has a USD bank account.

A week later, Katusa Gold closes their private placement, and the units are mailed out to all the investors that participated. On his subscription document, Joe indicated that his units should be sent directly to his broker. So his broker receives the shares and warrants from the private placement and deposits them into Joe’s brokerage account for him.

And that’s all there is to it – Joe’s finished acquiring yet another position in his stock portfolio through a private placement.

(By the way, Joe knows he can’t sell any of the shares of Katusa Gold he’s just received, because there’s a four month hold on his shares. He has no intention of selling though – he wanted $50,000 but only got $20,000 in the private placement, so he’s going to place some alligator bids on Katusa Gold in order to patiently acquire the remaining $30,000 he wants to allocate from his portfolio in several tranches. Needless to say, Joe’s example is one of pure fiction and not advice of any kind.)

12. Where Can I Find Private Placements to Buy?

A stock is never worth investing in just because it’s doing a private placement.

When I buy a private placement, it’s always in a company that I would’ve been willing to buy on the open market.

With that out of the way, it’s still not a bad idea to keep an eye on private placement news. Companies you already like and have on your radar might pop up, looking to do a round of financing. Or maybe seeing a financing with good terms leads you to do due diligence on a company you hadn’t looked at before. At that time, you might think it’s a worthwhile investment.

Unfortunately, private placements aren’t mainstream investments. You won’t find much news about them on business news, or in your Financial Times subscription. Google Finance and Yahoo! Finance won’t be of much help either.

Subscribe to our list and be alerted the moment we have Private Placement news for you.