It is somewhat ironic that while Iran has been under economically crushing sanctions since the US first applied them in 1979, that this time around they will actually have the best stack of chips at the bargaining table. The EU is caught between a rock—their recent Russian sanctions—and a hard place—the lifting of sanctions imposed on Iran over the past decades. On paper, it is actually in the best interests of the EU to remove the sanctions imposed on Iran.

A Brief History of Iranian Sanctions

Why was Iran sanctioned?

Iran has faced numerous rounds of sanctions over the years as a preventative against the further development of their military nuclear capability and their active support for terrorism. Sanctions have come by the way of the United Nations, EU, United States, Japan, South Korea, Canada, Australia, Norway and Switzerland. The five rounds of sanctions included the usual bans on supplies of heavy weaponry and arms exports, along with asset freezes, but there have also been bans on using SWIFT (the Western-controlled system for international banking transfers), and sanctions aimed at Iran’s oil and petrochemical sectors. The latter have really hurt Iran, as over 80% of the country’s GDP is tied to petroleum-based products. It is estimated the sanctions swung Iranian revenue from $96 billion in 2011 to a loss of $26 billion in 2012.

Much to the dismay of the EU parliament, during the June 2015 OPEC meeting in Vienna, Iran and Russia signed an agreement that would send Iranian crude to Russia, in return for Russian-made goods such as steel, wheat and petrochemicals. This strategic pact evades the sanction protocols devised by the Western world and further aligns Iranian and Russian interests.

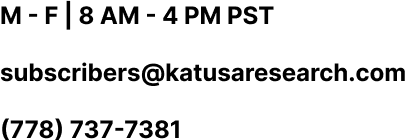

The results of lifting the petroleum-based sanctions on Iran are initially quite obvious. Increasing the global oil supply is a given, likely by a minimum 400,000 barrels within months of sanction removal and up to 1 million barrels a year or so later. This likely leads to an increase in the OPEC production quota, as no country wants to give up market share, which in turn will put downward pressure on the price of oil.

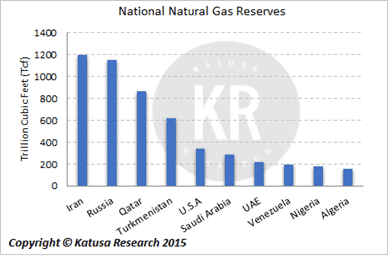

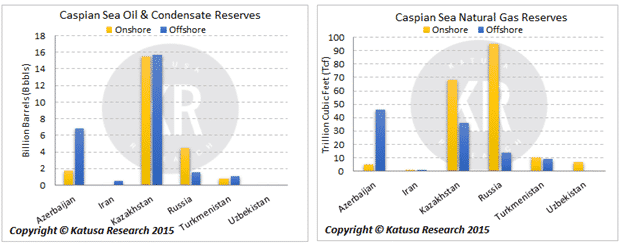

It’s a very big hurdle, but with the assets being world class and the EU being desperate to get away from Russian gas it is a price they are going to be more than willing to pay. The western pipeline (TAP) moves from Italy across Albania to the Greece-Turkey border. The 1,850km Trans-Anatolian Natural Gas Pipeline (TANAP) will link the South Caucasus Pipeline which connects Turkey to the Azerbaijani gas fields through Georgia. Azerbaijan’s state run firm owns 58% of the TANAP project, Turkey’s Botas holds 30% and BP owns 12%. Initial capacity will be 565 billion cubic feet per year that has expansion capabilities up to 2.1 trillion cubic feet per year.

The South Stream Pipeline is highlighted in red on the right, and illustrates 2.2 trillion cubic feet of gas annually being redirected away from the EU and into Turkey.

Under the EU’s Third Energy Package (TEP) a single company cannot own the pipeline through which it is also supplies the gas. Neither Russia nor Turkey is an EU member, and so neither is bound by the TEP, which makes the construction of Turkish Stream much easier. However, the construction of Turkish Stream is not the only issue at stake. The pipeline will have to stop at the Turkey- Greece border because of the TEP rules, given that Greece is an EU member state. Thus Russia will need its customers to buy its gas right at the border from the planned natural gas hub in Turkish territories.

The Caspian Sea: The EU Natural Gas Lifeline

On an annual basis the Caspian Sea produces upwards of 2.6 trillion cubic feet of gas and over 900 million barrels of oil. Historically the Caspian Sea lacks world class pipeline infrastructure, which is why the new TANAP pipeline is so important to Europe and the Caspian producers.

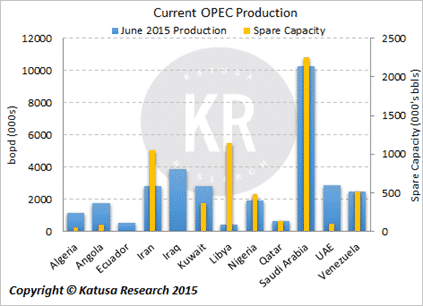

Current sanctions upon Iran make it difficult for the TANAP pipeline to move forward as capex is $11 billion and Azerbaijan can’t afford it alone. While Iran does not have significant Caspian production they do host massive other natural gas fields that would be ripe for EU markets. Furthermore, they have already stated they will fund a portion of the pipeline. Iran however, will only fund part of the pipeline project if sanctions are removed; otherwise, they would have no interest in helping Europe out.

You can see the European dilemma. On one hand they have Russia, which at this point is determined to make life difficult for EU citizens by cutting off natural gas. On the other hand, they are faced with the decision to remove sanctions on a country that for decades had a built up an extremely dangerous nuclear program. Furthermore, the Iranians and the Russians owe nothing to Europe themselves as demonstrated by their own barter agreement that bypasses Western world imposed sanctions. Europe must solidify a positive relationship with Iran moving forward or Caspian and Iranian gas is going to end up in someone else’s hands.

And worse than that, Europe will have no natural gas.