What the New York Times didn’t tell you, and the Real Threat to US Energy Security

In a recent front-page article in the New York Times by Jo Becker and Mike McIntire, Russia’s dominance of the world energy landscape was brought to America’s attention. In the article, the writers described the importance of Russia’s national nuclear company, Rosatom, and its acquisition of Uranium One which has uranium producing assets in the US. The article summed up quite well how Russia has re-established its energy influence around the world, and the US has become incredibly vulnerable.

In the article, Jo Becker mentions my book, The Colder War and quotes me.

She contacted me a few weeks before this article went live, and had many good questions. I gave her the facts about the current state of the global uranium sector. She got my contact details from the WNFM (World Nuclear Fuel Market) where I am giving a keynote talk at their 42nd Annual meeting this June 7-9th, 2015 in Paris, France.

A terrific writer, Jo Becker has put together a very interesting article, which was the most-read piece in the NY Times that day. One can easily see why she has won a Pulitzer Prize.

However, before I get into the very important data on the state of the uranium sector, I would like to clarify a few things that were unfairly portrayed in the article.

The Christianson Ranch property the NYT article referred to is dormant and not producing, another clarification I wanted to make in the article.

I have received hundreds of emails and phone calls because of this article, asking about Ian Telfer’s and Frank Giustra’s involvement with President Clinton, as mentioned in the Times article.

My first personal interaction with Ian personally was in early 2012. He was on the board of Renaissance Oil Corp (ROE.VN) a junior oil company that I saw great potential in. Through a mutual industry contact, Mr. Telfer and I were introduced to one another.

After months of negotiations regarding a private placement opportunity in this oil company, Mr. Telfer and I agreed on the terms of the investment. Ian and I were on opposite sides of the table here, as he was the company leader and I was the financier trying to get the best possible terms on the private placement.

I was impressed with Ian Telfer’s integrity in every aspect of the process. Everything he said he would do, he did.

A couple of years later, in early 2014, another round of financing was required for Renaissance Oil Corp (ROE.V). As expected, Ian not only did everything he said he would, he went out of his way to help me, with no benefit to him.

Through our many discussions about the financing for Renaissance Oil Corp (ROE.V) and the oil company going public, I shared with Ian that my first book was about to be published that fall. In The Colder War, I have a chapter on uranium, and how Russia has quietly consolidated its lead position in the global uranium sector and, as a result, the United States is now in a situation where there is a serious domestic threat regarding the American base load power generation. In the US, nuclear power provides 20% of its total base load electricity. And over the past 20 years, half of that has been generated by uranium that the Russians have supplied to the US utilities.

Ian Telfer not only read every page of my manuscript, he gave me unique insights that helped me improve my book.

Mr. Telfer has vision, and the ability to take that vision and bring it to life. What the New York Times article did not mention were the many net benefits that Ian Telfer and Frank Giustra brought to Kazakhstan’s uranium production profile and to the people of Kazakhstan.

In the last decade, Kazakh uranium production has increased by over 300%, and the country has become the largest uranium producer in the world.

That production increase was not because of the Russians.

The incredible increase by the Kazakhs in uranium production over the last decade was because of the North American innovation, technology and financing brought to Kazakhstan by the North American team. Another important aspect that was not mentioned in the article, that I felt was important, was the fact that the environmental and safety standards of the uranium industry in Kazakhstan had increased substantially because of the North American standards of Uranium One that were brought to Kazakhstan. The safety and working conditions of the average Kazakh uranium miner were also considerably improved by Uranium One’s involvement over the last decade in Kazakhstan.

Ian donated $3 million to Clinton’s charity. Ian did so, like any charity donor, because he believed in the cause.

Another well-known resource financier mentioned in Jo Becker’s New York Times article was Frank Giustra, and his role in the uranium transaction. I have known Mr. Giustra on a professional and personal basis since 2007.

I like Frank a lot.

We have not always agreed on business items, but I have a great deal of respect for his business acumen, his vision, intelligence, and integrity. Based on my business and personal interactions with Mr. Giustra, he is a man of his word.

Frank Giustra put out a statement on April 23, a day after the New York Times article. I believe Frank is an honest man. The one line from his statement that most resonated for me was, “This is not about me, but rather an attempt to tear down Secretary Clinton and her presidential campaign.” That sums up my feelings about the article.

The goal of my rant up to this point is to clarify where I thought the NY Times article was off with respect to Ian and Frank. I have nothing to personally gain from this. I just wanted to share my views about two individuals whom I have done business with. The Times unfairly portrayed them in a light that is not reflective of their true characters.

I wanted to point out all the good things both men have done not only with their charity efforts, but in improving the working conditions and environmental standards of the Kazakh mining industry. None of this was mentioned in the article.

Nevertheless, the Times article did get many facts right regarding the looming uranium crisis the US is facing.

The Russians have attempted to consolidate the uranium industry globally. The United States is now incredibly vulnerable as a result. The article correctly points out America’s current energy security Achilles’ heel. This is such an important topic that it should become a topic in this presidential election.

Russia has taken physical and political steps to further secure its grasp on the planetary nuclear energy market.

Russia has significant influence over uranium reserves and production and its weapon of choice has been its influence over energy rich countries like Kazakhstan.

About a quarter of the population in Kazakhstan is Russian. In addition, most of the government agencies and almost all businesses use Russian as the official language.

Kazakhstan is the world’s largest producer of uranium and has the second largest recoverable reserves of the mineral. Vladimir Putin’s relationship with the Russian-backed Kazakh President, Nursultan Nazarbayev, has established Russia as the uranium market mover. If you haven’t read my book, which will help you understand what’s going on in this important sector, here is a link to my chapter on uranium for free: click here to read the chapter on uranium.

In addition to its large reserves and production, Russia has a stockpile of highly enriched weapons-grade uranium and plutonium—enough that the country is estimated to hold over 5 times the world’s annual uranium production of just under 134 million pounds.

The misunderstood Fact of Underfeeding

The linchpin of Russia’s nuclear energy dominance lies in its enrichment capacity. Russian enrichment facilities can take low grade uranium tails with grades between 0.2% and 0.3% and turn them into the 3%-5% grade uranium required for fission in nuclear reactors for energy. By 2016 Russia will be capable of producing over 15 million pounds of uranium per year, or 40% of the US’s uranium demand.

After enrichment from ~0.7% U-235 to ~3-5%, the material left behind is what the industry calls tails. Tails still contain up to 0.3% U-235. This is where the price is important of SWUs, and why the Russians are benefiting from underfeeding while the US uranium companies are suffering.

The price of SWUs are much lower now than before Fukushima. Therefore the Russians can process tails with lower concentrations of U-235. In fact, the Russians have been able to produce 500% more uranium from tails post-Fukushima then just a year before the disaster at the same world uranium spot price. This is called an underfeeding market. We are currently in an underfeeding market.

Overfeeding would be the opposite situation; such that SWU’s are expensive and much less uranium would be produced from the tails because the grade of the tails would have to be much higher to be economic.

Let us make something very clear: the Russians are the ones benefiting from an underfeeding market; the US is at a disadvantage and domestic US production is suffering.

The reason is that the US DOEs not have the infrastructure in place that the Russians have, for the necessary enrichment that can take advantage of the underfeeding market we’re in. Underfeeding has contributed to the low price of Uranium, and that has created significant problems for US domestic production, which depends on mining rather than reprocessing tails.

Moreover, the Russians benefit in yet another way. Because they can reprocess more tails, the Russians have less radioactive material to dispose of.

President Obama’s Unintended Consequences

Ironically, President Obama has done more to help the Russians to execute their global nuclear agenda than anyone else in the world. This was something completely neglected in the New York Times article. Pre-2013, the US Department of Energy (DOE) had a cap on its uranium sales. Historically, the DOE followed the following two guidelines:

- DOE sales would not exceed 10% of the total annual uranium fuel requirements of all US nuclear plants.

- The DOE sales of uranium to the nuclear utilities would not occur at a price below that of a domestic uranium producer’s cost of production.

President Obama changed those two guidelines in 2013, and he could not have chosen a worse time to do so.

President Obama’s plan was well-intended but his advisors were short sighted. The president intended on using the DOE sales of uranium to generate $250 million annually for past clean ups on historic sites with environmental issues.

The unintended consequence of his actions is that President Obama has cannibalized the domestic US uranium production industry by selling strategic reserves into the open market, which in turn, has flooded the market. The uranium industry is a much smaller industry than oil, natural gas and coal. Thus, the uranium lobbyists do not have as much influence as the other sectors in Washington. For example, the four states involved in uranium production—Texas, Nebraska, Wyoming, and Utah—are all Republican states, hence you can see why Obama cares little what they have to say.

Therefore, Obama threw out both of the DOE’s historic guidelines listed above, and today we have a situation where the US has helped create the environment for the Russians to execute their global agenda on uranium. Way to go, Obama!

A Different type of Nuclear War

Most of the US headlines in the energy sector are about shale oil and gas, and there is some mention of coal. Uranium rarely, if ever, gets any coverage. However, it should, and it will, get a lot more coverage very soon.

The US is about to be hit with a shortage of a key strategic resource in its energy landscape.

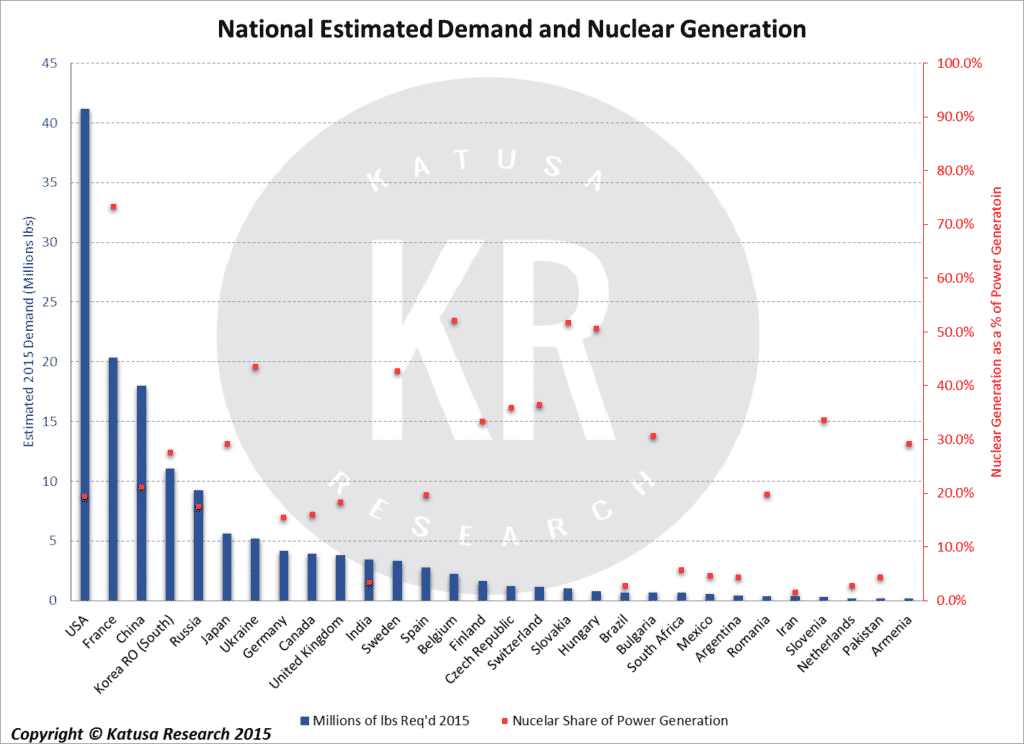

The US is the largest consumer of uranium in the world. As noted earlier, 20% of its energy needs are satisfied by nuclear energy.

The

Some of the rest comes from DOE sales or is imported from friendly neighbors in Canada and Australia. However, the largest imports come from weapons-grade downblending from Russia.

Downblending allows Russia to turn its nuclear warheads with uranium grades over 20% to the 3%-5% uranium required by nuclear utilities. As mentioned earlier, for the last 20 years, the Russians supplied the US with uranium to power 10% of its total domestic energy needs.

The Obama government depleted 30% of the DOE’s 160 million pounds of uranium from 2008 to 2013. Based on 2015 uranium requirements, this means the DOE’s reserve life for US demand is anywhere between 3-5 years. It took over 50 years to build up that stockpile. This is not what you call national energy security.

Japan plans to restart 4 of its 54 nuclear reactors this year. The Japanese government has also stated that it plans to get 2/3 of its nuclear reactors online in the next 4 years. That means that in the next 4 years approximately 14 million pounds of uranium per year will be needed to meet the Japanese nuclear demands; almost matching the demand expected to come from China in 2015.

From Underfeeding to Overfeeding

When the nuclear restarts in Japan happen, the uranium sector will go from underfeeding to overfeeding, which means higher cost to process tails and the price of uranium will rise with it.

In addition, there will be growing demand from China and India. Both will be bringing online significant nuclear capacity over the next four years. China’s uranium demand alone will increase by over four million pounds next year.

India has recently signed a long-term supply deal with Canada to help meet its demand moving forward. On April 15, 2015 Cameco Corp. (CCJ) signed a 5 year deal that would provide India with 7.1 million pounds of uranium annually until 2020. India will be doubling its current demand for uranium to 3.6 million pounds per year by 2017.

The US Dilemma

The US is losing the race to secure global sources of uranium supplies. With the media and most analysts focused on how the shale sector will survive the new reality in oil, there is a global colder war developing in the nuclear sector. It’s one that the US is losing.

Uranium is very different from oil or natural gas. Significant production of uranium occurs only in a few countries. This is a high-risk proposition for those who depend on imports of uranium.

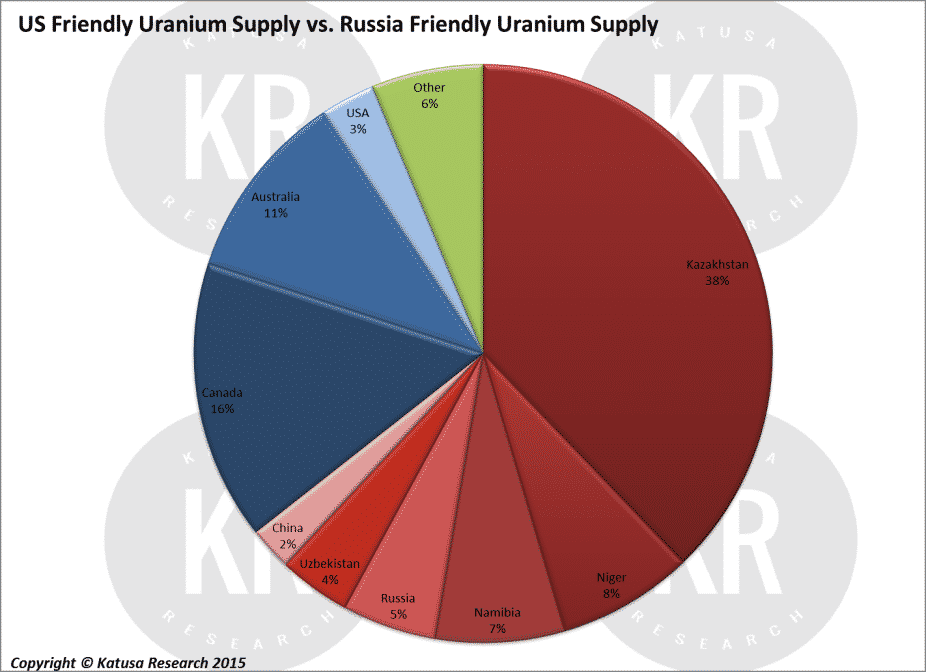

From the data below, you will quickly reach the same conclusion I have; the US will need to jump-start their own uranium production and fast. The red bars in this graph highlight countries producing uranium that would have their interests aligned elsewhere than with Washington.

Kazakhstan is highly tied to Russia. One can guarantee that Putin will make sure that the Americans won’t get their hands on any Russian or Kazakh yellowcake without his blessing or on his terms.

The US could rely on Canada and Australia for imports of their uranium; however, neither country can supply enough to fulfil the American demand. More importantly, both Canada and Australia have signed long-term off agreements with India and China. This means there is even less uranium available for US imports.

The USA and France are far and away the two largest consumers of Uranium in the world; however, China is catching up fast.

Currently for the major consumers of uranium, with the exception of France, uranium makes up well under 25% of the nation’s total generating capacity. The energy content of uranium is approximately 3 million times greater than that of fossil fuel.

To put it in perspective; a tenth of an ounce of uranium contains the equivalent energy of 6,613,868 pounds of coal. Furthermore, we know that nuclear is a significantly cleaner option for countries such as China or India who are suffering from their own versions of the Airpocalypse.

There are 64 new nuclear reactors that could be online as soon as 2024. While this a significant number, a more useful approach is to look at the number of reactors currently under construction. Regardless of which numbers you use, demand is set to increase dramatically. Below are all the nuclear reactors that are currently under construction.

Now include 2/3 of Japan’s 54 reactors, and you get the picture for what the demand for uranium will be in the near future.

Putting this all together into a single macro chart from the World Nuclear Association, one can quickly see that there is a serious need for new uranium production to meet demand.

US Domestic Production

The nuclear sector is a cyclical industry. However, the quantity of exploration work always trails the price of uranium. 1 in 3000 exploration targets ever becomes an economic mine. The odds of finding an economic geologic anomaly are very low. Not to mention, obtaining the financing required to build the mine will always be a challenge.

Permitting is also a nightmare in North America, so bringing new mines online is no easy task. Currently only a small handful of companies have commercial production around the world. Below are the net produced uranium pounds for each company.

Kazakhstan is producing almost 60 Million pounds of uranium. KazAtom is the state owned uranium producer, and the Russians have very close ties with KazAtom. With President Obama’s sanctions against the Russians over the past year, look for Putin to seek revenge in an unassuming way, and KazAtom is just the platform. Also under the influence of Russia is Navoi, the Uzbekistan national uranium producer. Both countries were part of the Soviet Union. We can see that, as with national production, the US DOEs not have too many friends in the corporate world. Red bars highlight companies whose interests lie outside the United States.

On the small cap side, there are 4 producers that have operations under way. Energy Fuels is the largest of the producers but while they produce more, the production comes with a higher opex and conventional mines are harder to quickly ramp production than “in situ recovery” (ISR) mines.

Through my research and management of my hedge funds I have been fortunate to have had the opportunity to see all of the US uranium mines that are currently in operation.

Depleting US Reserves

Before I move on, let me explain the difference between reserves and resources. Resources are how much uranium or “ore” is in the ground. Reserves are classified as the amount of economic uranium in the project at a specific price. Reserves are much more critical to a project then resources. Calculating the Reserve Life Index (RLI) of each company provides a quality measurement of the life span of a company’s assets (Reserves / Annual Production).

Another way to approach the RLI calculation is to look at total reserves divided by nameplate capacity. Nameplate capacity refers to the maximum quantity a company is legally permitted to mine on an annual basis.

We can take this a step further, however, and talk about something that no one else in the world is talking about. The ISR decline curve.

Just like a shale well in the Bakken, in which up to 70% of the well’s oil is recovered in the first year, one can apply similar math to uranium ISR production. The groundwater fluid from the injection wells is pulled underground to the extraction wells and is pumped to the surface plant where the uranium will be extracted. The cycle is repeated, and the groundwater is recirculated, over and over. Each time the process is repeated there is less uranium in the ore body; as a result, less uranium is extracted above ground. This leads to a decline curve just like oil.

The average decline in an ISR well field is a conservative 25-40% annually. Using a very basic example, if the initial ISR well production is 100 lbs of uranium, at the end of year 1, production will be closer to 60-75 pounds of uranium. So just like in oil or natural gas production where companies are forced to repeatedly drill new wells to hold production constant, the same can be said for uranium production.

At high uranium prices this is not a hindrance, because a company should be trying to maximize production anyways. However, in a low price environment where they are forced to drill new production and injector wells, just to keep output stable and meet their offtake agreements, they are losing money on every pound of yellowcake they produce. Now allow for permitting and financing delays, and you can see how valuable current permitted reserves are.

US Permitting Headwinds

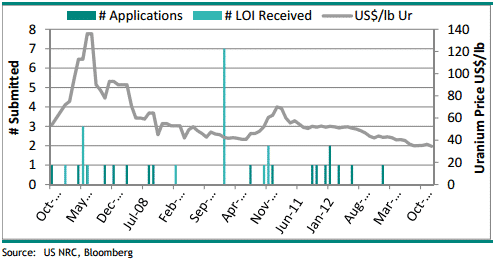

The growth of ISR in the US has been significantly slowed by regulatory issues. Unsurprisingly in the US, the regulatory agencies were unprepared for the ISR ‘boom’ triggered by all-time high uranium prices — these approached US$138/lb in June 2007 (up from US$70/lb six months earlier). This was the catalyst that led to regulators receiving seven ISR permit applications (or Letters of Intent, LOIs). The majority of these were between May and June 2007, although January 2010 also saw a high level of activity.

Wyoming pioneered ISR mining in the 1960s, and by 2008 only three companies had ISR mines in operation, and these had been permitted in 1987 & 1992, 2002 and 2006. Furthermore, the mine permitted in 2006 was of a pre-existing mine that had closed down in 1999. So really, the US regulators had only permitted one new ISR project over this time frame. This means that US regulators have only permitted a few ISR projects in the last 19 years, averaging a 6 year life span for attaining permits.

Barriers to entry create a solid investment thesis for all current uranium producers. It is near impossible for a company to capitalize on a short term bump in uranium prices with having to wait multiple years just to get a permit.

When properties get overvalued and prices drop, they become uneconomic and lose money. This causes producers to shut down their operations or worse yet be stuck—as most of the producers are—in long-term production contracts that force the company to deplete its reserves while realizing a significantly lower price than what the mine was designed for. Having the ability to slow down production and not deplete reserves while lowering both revenue and costs is a distinct advantage for uranium producers during a tough market. More exciting, however, is the valuable leverage they attain by being unhedged and not pinned to long-term contracts. The current spot price is $35.25, and as prices move back to the $50-$60 level and higher, a company that is unhedged and not tied to contracts becomes significantly more leveraged to the upside.

Ur-Energy and Uranerz are both prime examples of companies tied to the price and production requirements of a long-term contract. In their recent MD&A they state all their contracts are protected via price floors and ceilings. While this stabilizes cash flow, the main concern is the depletion of critical reserves in a depressed market environment, and that leaves the shareholders little upside on a longer-term sustained basis.

Uranium Energy Corp, on the other hand, is the only unhedged uranium producer in the world. It has the capacity to produce up to 2 million pounds from the Hobson plant, and when uranium prices do correct, UEC shareholders will benefit from the maximum leverage to the uranium price appreciation.

Let’s extrapolate this idea of staying unhedged over a number of years. It becomes a significant drag on cash flow if you hedge when the price of uranium increases. This leverage and upside potential for UEC is best exemplified through the cash flow per share chart below. While none of the companies currently produce 2 million pounds per year, we have adjusted to each company’s nameplate production capacity using current costs. By modeling the cash flow at $50, $55 and $60 we can see the per share growth across the board with the best cash flow per share in the comp group coming from UEC.

Who will the Big Funds Buy?

Liquidity is extremely important in the junior resource sector. There’s nothing harder or more frustrating than not being able to enter or, more importantly, exit a position. The 3 month volume average for the junior uranium producers is a no contest, with UEC’s volume coming in at 3 times higher than the nearest junior. In fact, something major funds such as Blackrock (who is a large shareholder of UEC) have recognized, UEC is more liquid than their peer group combined by over 200%!

Moving Forward

The best RLI both on a current production and nameplate capacity basis provides long-term growth potential for UEC shareholders. By not being hedged to either spot or the long-term price in the current depressed market, UEC enjoys the distinct advantage of maximum leverage as the only unhedged uranium producer in the world.

I have been to the site of every US publicly listed uranium producer, and have seen firsthand the difficulty of putting a mine into production. Every single producer I mentioned above should be lauded for achieving producer status. Mining is a tough business, and I believe all of the companies mentioned above will do well. The time period between the exploration of the deposit to the actual production of yellowcake takes roughly 10 years for most uranium mines in the US. After going through such a difficult process, and beating the 1 in 3000 odds, why deplete your reserves in a down market? I am long UEC.